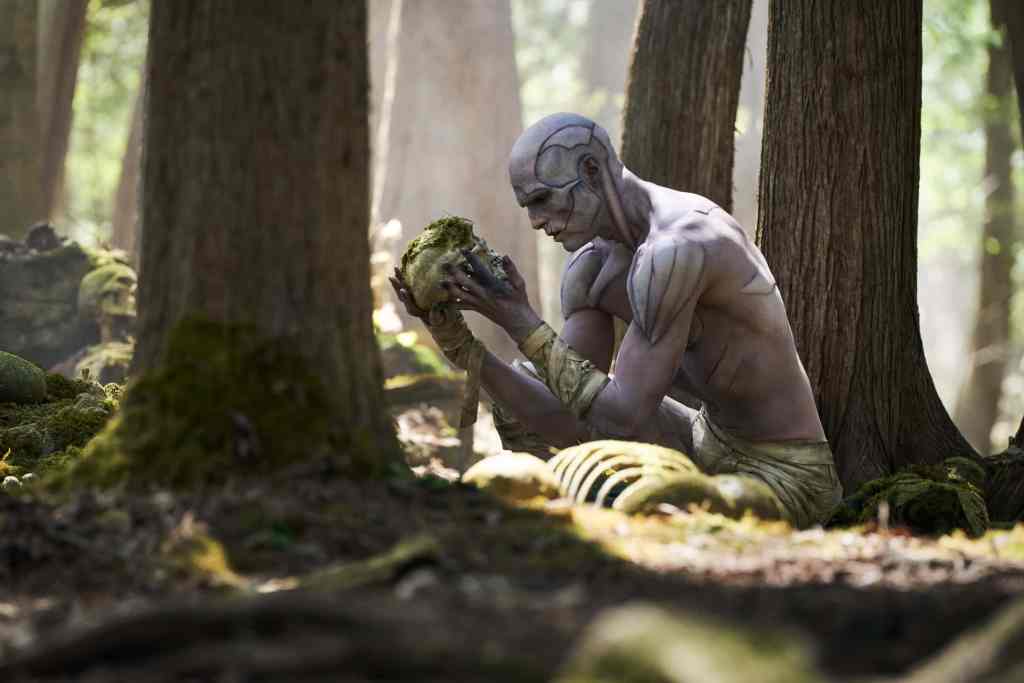

For Guillermo del Toro, monsters were never villains. They were mirrors, symbols of love, and survival. His long-planned Frankenstein, now arriving on Netflix, feels like the film he was always destined to make.

It gathers every idea he has chased across thirty years of storytelling, from Cronos to The Shape of Water to Pinocchio, and turns them into a single confession about what it means to create and to be seen.

Del Toro once said that “monsters are my church.” In Frankenstein, that belief becomes literal. The film transforms Mary Shelley’s cautionary novel into a kind of spiritual autobiography, a work about fathers, sons, and the weight of inheritance.

A Story Decades in the Making

Del Toro has carried Shelley’s book with him since childhood. He describes it as his “white whale,” a project he’s rewritten for years but only filmed when he felt he could tell it from the heart, not the head.

Across his filmography, creation and compassion always collide, the vampire’s curse in Cronos, the lonely amphibian god in The Shape of Water, the grieving carpenter in Pinocchio. Each story circles the same question: can love survive fear?

Frankenstein becomes the answer. Here, Victor Frankenstein is not a mad scientist but what del Toro calls “a misunderstood artist,” played by Oscar Isaac as a man who mistakes mastery for devotion. The creature, embodied by Jacob Elordi, is his reflection, the child, the conscience, and the echo of everything Victor refuses to accept in himself.

Monsters as Faith, Not Fear

Del Toro has always treated monsters as sacred figures, and Frankenstein makes that reverence visible. He describes the film as “an epic about how trauma and love are passed down.” That idea runs through every frame: the baron’s cruelty, Victor’s obsession, the creature’s hunger for affection.

Where Shelley’s novel warned against ambition, del Toro reshapes the myth into a parable about forgiveness. His monster is not a punishment but a survivor. Through him, del Toro gives shape to a belief that runs through all his work, that the grotesque and the holy are two sides of the same act of creation.

A Legacy Work

For Del Toro Frankenstein a “culmination,” and it feels like one. Visually, it closes a circle that began with the handmade alchemy of Cronos and the fairytale melancholy of Pan’s Labyrinth. The sets are physical, the colors symbolic, red for bloodline and guilt, silver for resurrection, blue for grace.

Del Toro has said he wanted the film to feel “tactile and eternal,” as if it could have been built from the remnants of his own imagination. Even the Arctic setting, a return to the novel’s beginning, mirrors the isolation of his first films.

The story’s end, a dying Victor calling his creation “son,” the creature forgiving him, is the clearest statement of what del Toro has been reaching toward for decades. His monsters are no longer metaphors for horror. They’re vessels for mercy.

What Del Toro Leaves Us With

Frankenstein is more than a reimagining of a gothic classic; it’s the emotional cornerstone of Del Toro’s career. After decades of finding beauty in decay, he gives his monsters something they’ve never had before, peace.

That’s why this version feels final, even personal. Del Toro has often said he makes films to understand himself. With Frankenstein, he seems to have done it.

Key Details: Frankenstein

- Release dates: In select theaters October 17, 2025; streaming on Netflix November 7, 2025

- Director & screenplay: Guillermo del Toro

- Based on: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley

- Producers: Guillermo del Toro, J. Miles Dale, Scott Stuber

- Main cast: Oscar Isaac (Victor Frankenstein), Jacob Elordi (the Creature), Mia Goth, Felix Kammerer, David Bradley, Lars Mikkelsen, Christian Convery, Charles Dance, Christoph Waltz